Why Does Russia Want The Arctic? (1/2)

A Geopolitical Analysis of Northern Sea Route and Siberian Continental Shelf.

In the summer of 2007, the Arctic region hit headlines around the globe. Media outlets ran with a hazy picture of a blue, white, and red flag, planted by a Russian scientist as a publicity stunt 4000 metres below sea level at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean. Not long after, it was reported that the Arctic Oceans sea ice levels had dropped by 38 per cent below average – a record drop. New questions were being asked. Who owns the Arctic? Is the Arctic still an exceptional region? Will Arctic demarcation be peacefully resolved? Will it resemble Antarctica, or follow the South China Sea with claims enforced by military coercion?

History tells us un-demarcated regions that have vast resources and geopolitical opportunities attract competition and conflict. Furthermore, considerable ambiguity over Russia’s foreign policy ambitions has fuelled a wave of concern over its Arctic intentions. Russia became the first state in the contemporary era to break the post-Cold-War geopolitical tranquillity by invading the territory of another state. With post-Cold-War international norms seeming increasingly fragile, media outlets are given licence to run with sensationalist headlines, e.g. “Are NATO warships about to start WWIII in the Arctic?”. Politicians speak of “New threats to the Arctic and its real estate”. And academics ponder if we are witnessing a regional ‘Security Dilemma’, fuelled by the apparent return of great-power politics on the world stage.

Russian militarisation within the region is not in doubt. The construction of airfields and bases in the vicinity of the Arctic Ocean and the deployment of advanced military technology in the region has been well documented. This article addresses the question of geopolitical purpose. What is the value of the Arctic? What does Russia want to do with the Arctic? This article will focus on the rationales that can be thought of as intra-regional, meaning that Russia’s interests and designs are meant for the Arctic Region. The next article will explore factors I judge to be extra-regional, in that they happen to be in the Arctic, but have a non-Arctic purpose.

The Northern Sea Route

Just like the United States historical interest in building the Panama Canal, and China’s current interest in controlling the South China Sea, Russia seeks relative power derived from the control of access to economically important spaces. Russia asserts that the sailing route between the Barents Sea and the Bering Strait is an internal water, on the basis of its de-facto control over the area and the historical legacy of Russian development in the region.

Ice extent and thickness are critically important for navigation, and the year-round prevalence of sea ice made passage only possible for icebreaker vessels or a fleet escorted by an icebreaker. Since the 1990s, accelerated melting of sea ice has been observed, dropping to its lowest ever levels in 2012. The drop in sea ice reflected an upsurge in usage, in 2010 only four transits occurred on the route, which rose to 71 in 2013.

The NSR offers a viable route for transporting cargo for two purposes. The first is to take resources extracted from the Russian Arctic to markets further south. The second is the vision of the route as a new global maritime highway, offering a new, shorter connection between the pacific markets of East Asia and North America, and the Atlantic markets of Europe and North America. All Asian cities north of Hong Kong could reach Europe more rapidly via the Arctic than via the Suez Canal.

The Siberian Continental Shelf

The concept of internal waters is heavily disputed, is not recognised as a legitimate way to claim control over an area of sea and is usually not recognised by other countries. The claim ‘internal water’ is usually justified to charge foreign vessels a transit fee rather than to claim territory. The most important way in which Russia is attempting to claim a vast area of the Arctic is through the geological phenomenon called continental shelves. Continental shelves are found all over the world. A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water known as a shelf sea. Continental Shelves are used as justification by many states to claim further territory.

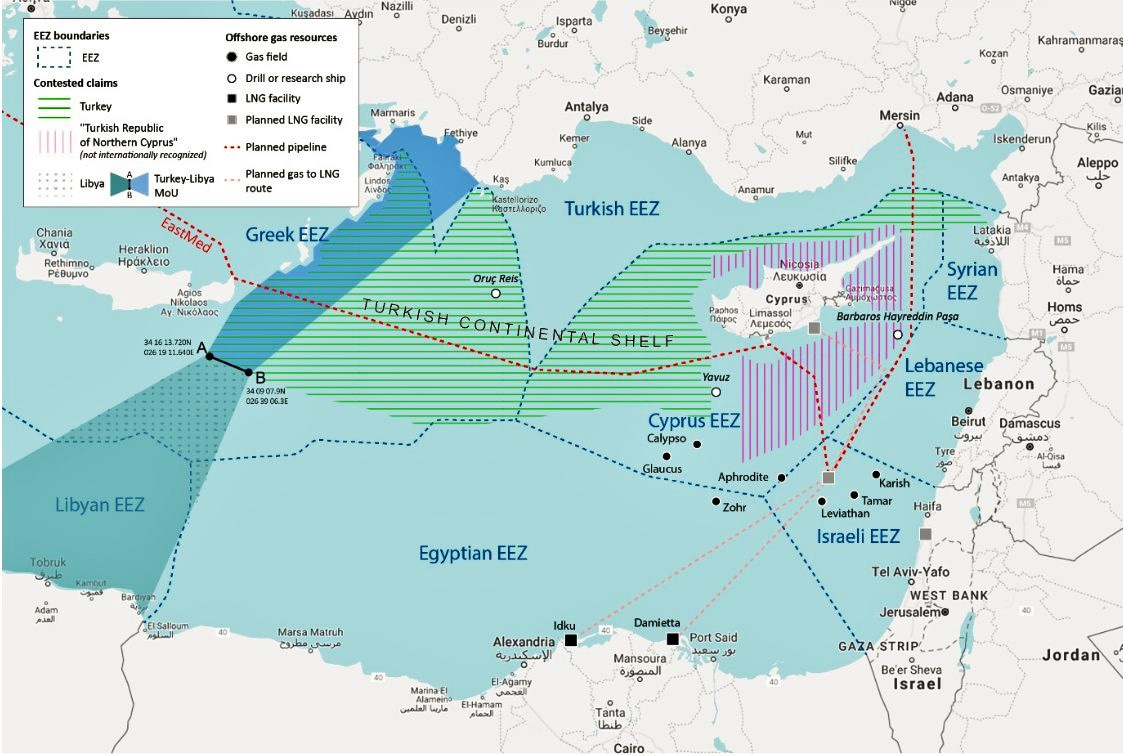

If a state gains recognition of territory up to a continental shelf, the seabed territory that makes up the shelf is called an ‘Exclusive Economic Zone’, in which that state has full, unilateral rights to the economic resources found within them (see example above). Most states with shelf claims are only concerned with pursuing unclaimed economic resources. This could be fish or undersea hydrocarbons such as oil and gas. Some also claim for military reasons. In the South China Sea, China is using its continental shelf claim to justify its construction of artificial islands that will eventually become naval bases.

The geology and rules surrounding shelf claims are very complex, yet an attempt must be made to understand them as they are the cause of several other ongoing geopolitical disputes in addition to the Arctic. A UN treaty called the United Nations Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) exists to arbitrate on claims. At its most simplistic, signatories of the treaty are entitled to full territorial control up to 12 Nautical Miles (nm) off their coastline, and up to 200nm as an exclusive economic zone if the zone does not impede on the zone of another state. yet not every country has signed the treaty, with the most notable non-signatory being the United States.

A well-known dispute involving shelves concerns the small island of Rockall north-west of Scotland. The seabed is claimed by Britain, Ireland, Iceland, and Denmark, with all claiming that the island falls in their continental shelf, and therefore claim it and the vast area of the sea surrounding it as part of their territory. The dispute has been ongoing for several decades, with three inconclusive conferences held between the claimants between 2007-2011.

A more active and hostile dispute over a continental shelf in ongoing between Greece and Turkey, with both disputing the other claim to seabed territory in the Eastern Mediterranean. This has seen both sides attempt to form regional alliances to bolster their own claim, with Greece partnering with Cyprus, Israel, and Egypt to cooperate on seabed demarcation. Turkey requires a friendly government in Libya to validate its own claim, which explains why Turkey has militarily intervened in the Libyan civil war on the side of the GNA. Turkeys actions give a good illustration of how important continental shelves are in a state’s foreign and military policy.

Returning back to the Arctic, Russia has signed the United Nation’s Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) treaty and has formal international recognition for all resources up to 200nm offshore already. But recently Russia has asserted that the Lomonosov and Mendeleev Ridges are an extension of the Siberian Continental Shelf and thus claim the entire seabed as Russian territory. The claimed area spans some 1.2 million km sq and extends 350 nautical miles (nm) offshore.

The area claimed by Russia accounts for 52% of the total untapped energy resources in the Arctic region. Undiscovered petroleum is estimated at 66 Billion tons of oil equivalent (BTOE) and Gazprom has estimated the area to hold 632 BTOE of liquefied natural gas. For perspective, in 2011 the entire planet consumed 13 BTOE of energy. In addition, the region has vast deposits of phosphate, bauxite, iron ore, copper, and nickel. As the sea ice retreats and the region becomes accessible for economic activity, the huge economic and political potential of Arctic natural resources for Russia has become increasingly apparent.

It is these two reasons - control of the shipping route, and economic resources, that give the Arctic region economic and political value to Russia. It has been assumed that militarisation of the region is occurring in service of the accomplishment of these aims. Yet a deeper look at the economic and diplomatic value of the resources highlight throws up several questions.

The profitability of the shipping route is unclear and does not offer a firm reason in itself for why Russia is so interested in the region. The NSR’s geographical location between Europe, America, and Asia-Pacific does not, in and of itself, suffice to impact market-based principles. Its geological value as a line on a map does not determine its viability.

Although the ice retreat in summer is favouring trans-Arctic shipping, no research has indicated that the winter sea ice cover will disappear during this century. Unpredictable conditions almost always lead to delays in transit, offsetting the time saved through the reduction of distance, making the route wholly unsuitable for most container cargo, which operates on a strict, linear schedule. Even if container ships could transit on a reliable schedule, there are no en-route markets, significantly reducing its attractiveness compared to the southern route through the Suez Canal, which passes through some of the fastest-growing markets in the world today. This leaves bulk cargo, oil, gas and minerals, as the only other regular commercial option. Yet the shallow waters of the route limit the size of the ships that can successfully transit across it, ruling out cargoes where economies of scale are paramount in determining profitability.

Furthermore, it does not seem to be in Russia’s interest to militarise a dispute which is diplomatically working in their favour.

In August 2015, Russia resubmitted its claim to UNLOS for the area up to the continental shelf. A technical analysis of the Russian claim lies beyond my capabilities, although it would not be necessary, as Norway, Canada, and the USA have submitted counterevidence against Russia claiming territorial infringement. Even if claims are geologically valid, the commission is unable to assert decisions that disadvantage other states. In this scenario, the commission offers recommendations and invites competing sides to negotiate a delineation deal. Russia signed an agreement over seabed delineation in the Barents Sea with Norway in 2010. Though unpopular within Russia, the treaty has provided positive evidence that Russia is open to resolving territorial disputes through bilateral agreement.

It is also difficult to imagine a scenario in which Russia abruptly loses out to an Arctic competitor and is forced to resort to a seabed grab. Even if Moscow unilaterally declared its ownership over the vast underwater territory, military force could have only a symbolic role in asserting this declaration. Superiority in conventional power projection capabilities is difficult to translate into any tangible political advantages. Russia is a reluctant rule-follower regarding the continental shelf. International law plays in its favour, and it is in Russia’s interest to preserve the current arrangements. Increased assertiveness over the shelf through military symbolism may work against Russian interests in this regard, as it pushes other states to enhance their own realpolitik firmness in quarrels over resources with Arctic neighbours, which are unresolved in some form for all 5 littoral Arctic states.

I find it hard to believe that Russia’s interest in the region is down to these factors alone. Russia’s leadership are realists. there is little pragmatic sense in militarising a region that evidently does not require militarisation for these reasons alone. It follows that there are other reasons for military activity in the Arctic that may not be centred on the Arctic itself. Russia’s true motivations for the Arctic go beyond the mere economics of regional natural resource extraction and shipping. Russia’s strategic thinking can be found by looking globally. In the next article, I will explore the extra-regional factors that may help explain Russia’s geopolitical interest in the Arctic region.

Sebastian Rowe-Munday